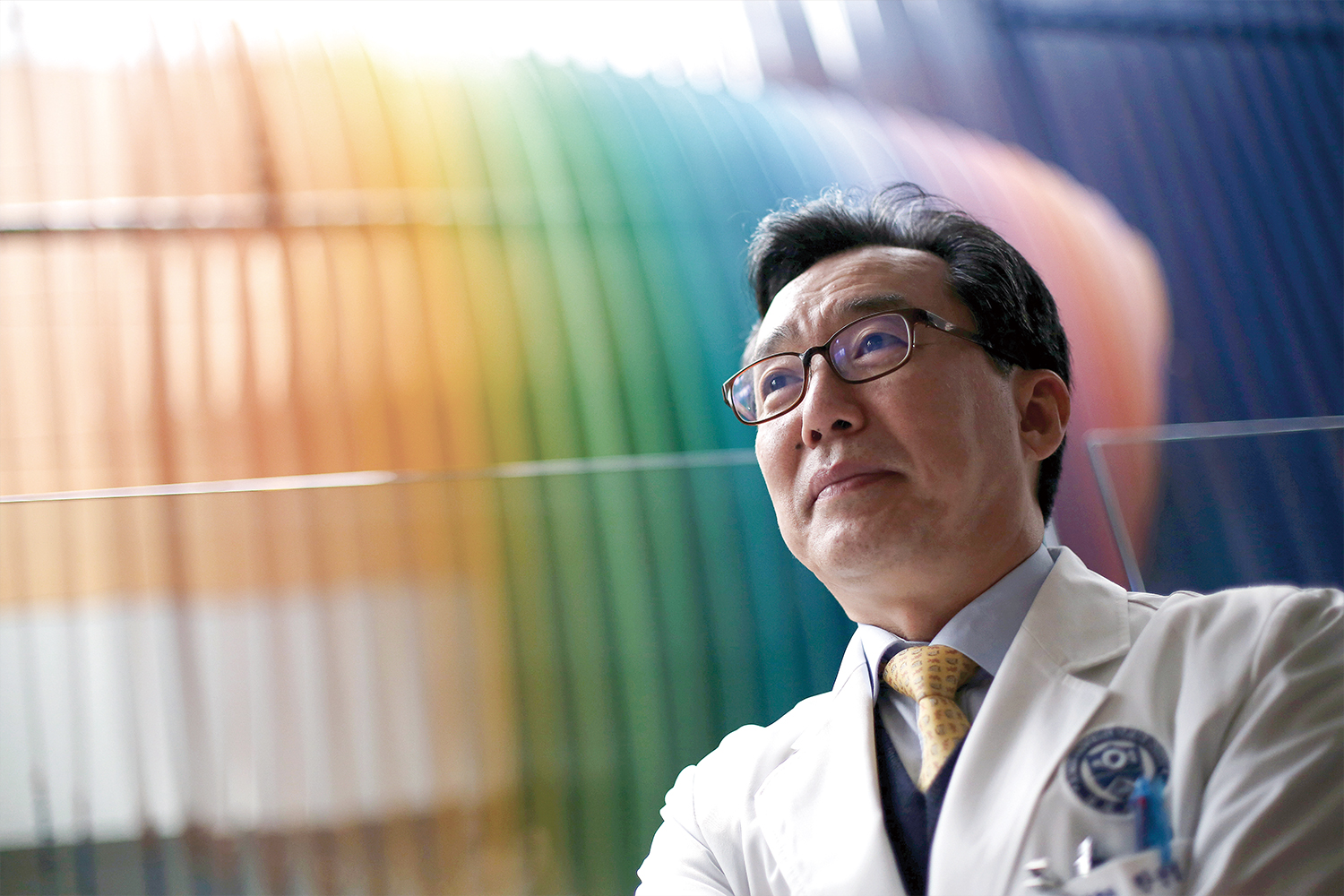

Han Kwang-hyub

Professor in Department of Internal Medicine,

Yonsei University College of Medicine

Han Kwang-hyub, one of the most noted liver disease experts in Korea, was the world’s first doctor to prove the effectiveness of concurrent chemoradiotherapy for the management of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. The founding member of the International Liver Cancer Association has been active in viral hepatitis clinical research since the mid-1990s.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may be the best-known virus in the world, but not the most lethal for Asia. While HIV kills about 250,000 Asians every year, liver cancer, which is mainly caused by viral hepatitis, kills 360,000 people in East Asia alone. Yet research for liver diseases does not receive the attention and funding it deserves, and the work is largely controlled by doctors and pharmaceutical companies from Western countries, Professor Han Kwang-hyub at Yonsei University’s Severance Hospital said. “Asian doctors should take the leadership in solving the problem that is affecting mostly the people in Asia,” Han, 61, said in an interview. He believes stronger and more frequent collaboration among Asian doctors can bring much-needed attention and investment to liver disease research. “Together, they can achieve a lot,” he said. “They need to share more research information about liver diseases, discuss their visions and set new directions for future studies.” This belief led him to host the inaugural Asia-Pacific Primary Liver Cancer Expert Meeting (APPLE) in Incheon in 2010, when he was the president of the Korean Liver Cancer Study Group. Since then, it has emerged as one of the most recognized conferences for liver cancer experts in the region. The purpose of creating the conference, which has now become an annual event, is to give doctors in Korea, Japan and China an opportunity to share their latest knowledge and opinion about liver cancer and other liver diseases, Han noted. He believes Asian doctors, with their significant clinical experience in treating liver disease patients, can provide valuable knowledge in liver disease research in a way that Western doctors cannot. “They deal with so many different cases, compared with Western doctors, but their clinical experience is often overlooked in Europe and North America,” he said. “But their knowledge could — and should — be used valuably to unravel the mysteries of liver cancer and hepatitis.”

One of the advantages of having significant experience is knowing when to apply certain drugs or other treatment methods to patients. “In other words, it can teach you a lot about timing,” he said. “Timing is one of the most critical parts of treating liver diseases. Certain drugs, for example, are effective at certain stages but not at others. Thus, doctors should know what drugs have to be used exactly when. If the doctor misses the timing, the whole treatment could be ruined,” he said. “Outside Asia, treating liver disease patients is mostly the job of gastroenterologists, who do not have much experience in treating liver disease patients, because there are few experts in the field.” One of the most important tasks of the APPLE is to establish treatment guidelines for liver cancer. “There are so many different treatment methods in Asia now. We want to examine them and establish reliable, evidence-based guidelines for them,” Han said. “More lives can be saved if we can provide better prognostic classification and better treatment strategies.” Han is one of the most noted liver disease experts in Korea. The founding member of the International Liver Cancer Association has been active in viral hepatitis clinical research since the mid-1990s. He also developed some of the new treatment methods that have proved to be more effective for liver cancer patients with certain conditions. Han is the world’s first doctor to prove the effectiveness of concurrent chemoradiotherapy, the use of chemotherapy concurrently with radiation for liver cancer patients. After receiving the therapy, end-stage liver cancer patients, who were initially expected to die within three months, lived for 11 months on average, according to his research. More strikingly, 15 percent of them, who were initially considered too serious to receive surgery, could receive it and recovered eventually, thanks to the treatment that improved their symptoms. Han said for now he is studying how to further improve the treatment’s effectiveness.

Fighting the main cause — viral hepatitis

Liver cancer is the sixth-most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. In Korea, the cancer is the No. 1 killer for men aged 40 to 50. Viral infection from either the hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the chief cause of liver cancer, accounting for about 80 percent of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer. Vaccination is the best available protection against HBV. There is no vaccine for HCV, so, for now, the best advice for avoiding the virus, which is believed to be transmitted only through blood, is to be careful with needles. Thirty years ago, when Han started his medical career, there were few things doctors could do for patients infected with either virus. Today, thanks to advances in drugs, doctors can help turn the diseases into manageable, albeit still chronic, conditions, he said. “I am a part of a lucky generation as a doctor and researcher,” he said. “I was fortunate to start my career at a time when global pharmaceutical companies such as BMS and Glaxo Wellcome started to develop drugs for HBV and HCV. It was good news especially for Korea, which was one of the worst countries in terms of the diseases, when China was still isolated from anything from the West.” It was also a great opportunity for Han, who at that time had been developing his career as a researcher after training at Baylor University in Texas. He participated in developing new drugs with global pharmaceutical firms, which opened a new horizon for him. “Today, many cases of HBV and HCV can be managed with drugs to a certain degree, though doctors are still struggling with the issue of drug tolerance,” Han said. “Yet there is still no cure for the viruses. To develop effective drugs, doctors need to be more active in clinical research.”

Being open to creativity, collaboration

In terms of determining treatment options, liver cancer is one of the trickiest because it depends on many factors, such as tumor size, stage and the patient’s tolerance to certain drugs, Han said. “That’s why liver doctors have to be creative and be open to working with others experts,” he said. Creativity helped him come up with concurrent chemoradiotherapy in 1995, after learning about how radiation oncologists treated cancer. In 1999, he also started using radio-active isotope (Holmium-166) complex in liver cancer treatment — the world’s first doctor to do so. “The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety eventually approved the method, which proved to be effective in preventing the growth of early-stage tumors,” he said. “Throughout my career, I have realized the importance of creativity and collaboration with experts in other fields, and the two things definitely helped me get where I am today.”