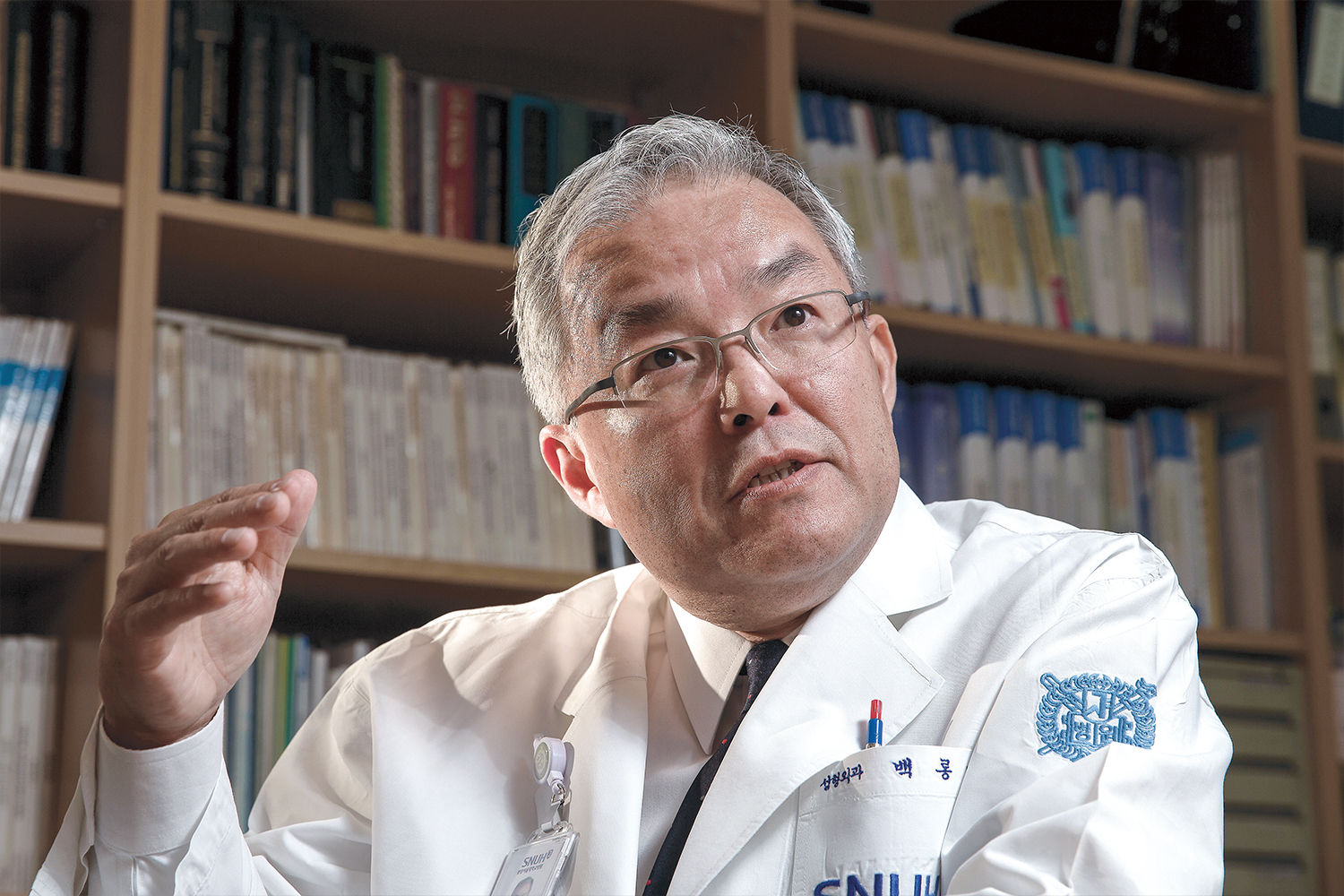

Baek Rong-min

Professor in Department of Plastic Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine

Baek Rong-min, one of the most renowned plastic surgeons in Korea, operated on thousands of children with cleft lip and cleft palate and other such conditions in Southeast Asia for 30 years. He is a younger brother of Baek Se-min, his “role model,” who pioneered in the field of plastic surgery in Korea.

Modern plastic surgery was born after the First World War (1914-18), during which hundreds of thousands of people were killed and injured. Around that time, New Zealand otolaryngologist Harold Gillies developed facial surgery techniques to treat those who were permanently disfigured. Even though the world’s major wars have long ended, many still need plastic surgery, including those who suffer from cleft lip and cleft palate — birth defects that occur when a baby’s lip or mouth do not form properly during pregnancy. According to the World Health Organization, one in every 500-700 babies is born with a cleft lip and/or palate. Cleft lip and cleft palate can usually be treated with surgery. If untreated, a child with a cleft lip and/or palate will be unable to eat properly and speak intelligibly. Over the past 25 years, Prof. Baek Rong-min of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital performed operations on more than 3,500 children with the defects in Southeast Asia, where many do not have an access to medical services. “This is one of those things that I want to do for the rest of my life,” the 57-year-old said in an interview. “The work has been hard but also very rewarding.” Cleft lip and cleft palate occur when the tissues of the upper jaw and roof of the mouth fail to fuse during gestation. The defects can have a serious psychological impact on a child, particularly as he or she gets older and begins to mingle with other children. Since children with the defect cannot speak clearly, many get ostracized. Baek said he feels the burden of the defect on the children. Thus, he has dedicated himself to treating poor children with facial deformities in developing countries, including Vietnam, Myanmar, Indonesia, Mongolia and Uzbekistan.

“The surgery takes only about one or two hours, but for every child, I understand that this is the most critical time of his or her life,” he said. “The child will have to live with whatever result I get for the rest of his or her life. The pressure is big.” But seeing the joyful smile on his patient’s face after surgery is well worth the stress and many other difficulties that he encounters in his job such as hours of bumpy road trips and the 40-degree heat in Vietnam, Baek said. In recent years, Baek has been systemizing his surgical know-how and methods for facial deformities. He said he wants to make it easier for anyone to learn how to do surgery easily with pictures and videos. “As more doctors become capable of treating conditions such as cleft lip and cleft palate, more children will be able to get benefit from them,” he said.

As part of the mission, for the last decade, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital has been inviting doctors from Southeast Asian countries, mostly from Vietnam, to train them. Smile for Children, a nonprofit organization led by Baek, has also been giving medical devices to countries in need and has been helping them improve their medical infrastructure. Baek’s humanitarian work in Vietnam began in 1996, only four years after Korea and the nation reestablished diplomatic relations. “People were not friendly at the beginning,” Baek said. But his years of selfless efforts have touched the hearts of many patients, their families and government officials in the country. In 2014, he became the first Korean to receive the Audrey Hepburn Humanitarian Award for his contributions to improving the lives of children here and abroad.

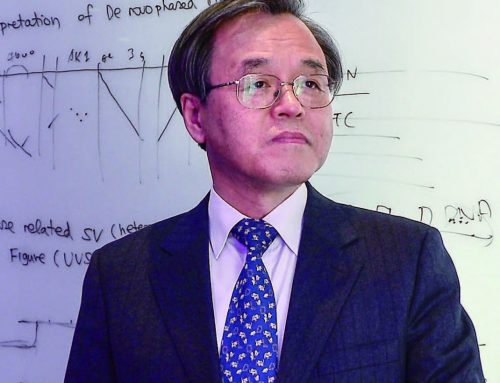

A role model brother

Even though it was his own decision to become a doctor and to specialize in plastic surgery at Seoul National University, his brother, Baek Se-min, 73, largely shaped who he is today. “He was my role model,” Baek Rong-min said. “He helped me grow not only as a surgeon but also as a person. Without him, many things would have been very different.” Baek Se-min was a pioneer in the field of plastic surgery in Korea. After graduating from Seoul National University in 1967, he went to the United States to study and worked there until the early 1980s. Although his career at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City started to take off, he decided to return to Korea to realize a bigger vision. When he returned, he brought with him many advanced surgical techniques, including the one for double-jaw surgery, which involves cutting and rearranging the upper and lower jaws. “My brother was a good teacher,” Baek Rong-min said. “Instead of telling me what do to, he showed me how. But, if anything went wrong, he punished me harshly. He was very strict.” It was Baek Se-min’s idea to help Chinese children with facial deformities in the early 1990s, even before Korea and China started diplomatic relations in 1992. And he is the founder of Smile for Children, which was established in 1995. The doctor, who had great compassion for children, believed financial difficulty should not prevent any child from getting the necessary treatment. “I’m just carrying on his legacy,” Baek Rong-min said. “When I was a medical student, I wanted to become a great doctor without knowing what it meant exactly. Looking back, I think I have achieved my dream, or at least part of it, thanks to my brother.”

‘Nothing wrong with getting surgery to look beautiful’

Nowadays, an increasing number of women get plastic surgery to look beautiful. Korea is known as the best country for getting work done. However, a series of recent incidents have highlighted the risk of undergoing plastic surgery to improve one’s look, including one incident involving a Chinese woman who was declared brain dead after undergoing surgery on Jan. 27 2015. “There is nothing wrong with people who want to be more beautiful,” Baek said. “I think the problem lies rather in the people who do the job.” Under the Korean system, doctors should have four years of training to become a specialist in one particular field. However, the law allows anyone with a medical license to perform surgery in whatever field they want, albeit they cannot promote themselves as “plastic surgery specialists.” “As far as I know, 60 to 70 percent of those who practice plastic surgery are not specialists,” Baek said. “I think it is wrong to think that anyone with knowledge of techniques but without respect for human life and dignity can do the job.”

댓글을 남겨주세요