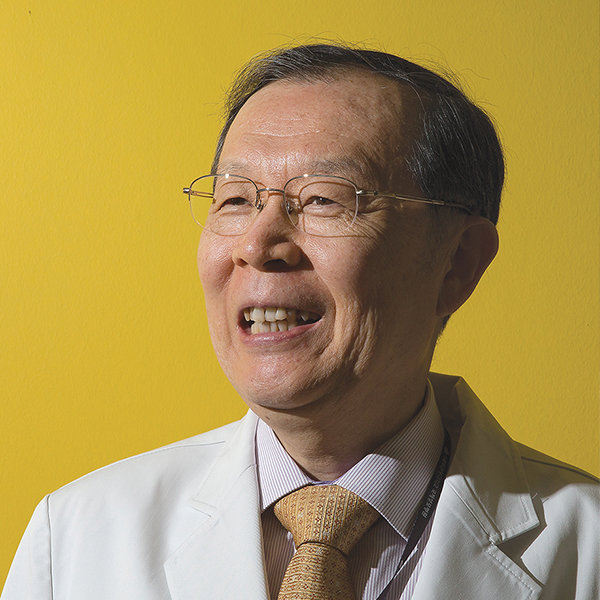

Bang Dong-sik

Professor in Department of Dermatology, Catholic Kwandong University International St. Mary’s Hospital

Bang Dong-sik, one of the world’s most renowned Behcet’s disease experts, founded the first Korean clinic dedicated to the disease in 1983. Throughout his career of more than 30 years, he treated over 10,000 patients and published more than 250 articles on the subject while playing a critical role in making guidelines for the disease.

가톨릭대학교 서울성모병원 병원장 승기배 / 심현철기자 shim@koreatimes.co.kr

Living with any illness can be a challenge, but even more so for patients with Behcet’s disease, who face some uniquely difficult problems. Even getting an accurate diagnosis is already hard because there is no single test that can identify the disease. Besides, symptoms could vary among patients and no single medication or treatment works for every case. “Behcet’s disease is something of a medical mystery,” Bang Dong-sik, a dermatologist at Catholic Kwandong University International St. Mary’s Hospital, said in an interview. “But I have found some better ways to diagnose and manage the disease.” Behcet’s disease, first defined as a specific disease in 1937 by Turkish dermatologist Hulusi Behcet, is characterized by a triple-symptom complex of recurrent oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers and uveitis. The rare autoimmune disorder could attack the blood vessels anywhere in the body, causing ulcers and lesions in organs. “Having Behcet’s disease means you have to fight inflammation every day for the rest of your life,” Bang, 66, said. “Just imagine you have several mouth ulcers that never go away. You have to cope with constant pain from the moment you wake up. It is very difficult, not only physically but also psychologically.” The disease affects each patient differently. Some show just mild symptoms such as canker sores or a few mouth ulcers, but others could get meningitis, an acute inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, or lose their sight permanently. “Patients may not notice the disease for months or years until serious signs start to appear,” Bang said. “Symptoms may or may not last for a long time, but if they disappear, they come back, often with other symptoms. That is the typical pattern.” Bang is one of the world’s biggest Behcet’s disease experts.

Over the past 30 years, the scholar has published more than 250 articles on the subject, helping to set up clinical guidelines for the disease. “Since there is no one way to identify the disease, physicians make a diagnosis based on their clinical experience. But the problem is that few of them are familiar with the disease,” he said. Accurate diagnosis is difficult because the symptoms do not usually appear all at once and there are other illnesses that have similar symptoms such as systemic lupus, Crohn’s disease and other forms of systemic vasculitis, he noted. Moreover, the causes of the disease are unknown. Some scientists speculate that patients may have inherited an immune system that is more vulnerable to the disease. Others believe the environment plays a role because the non-communicable disease affects mainly certain parts of the world (the Middle East and the Far East regions). Questions remain on the role of age as well. Although the disease can appear at any age, it mostly occurs in people in their 20s and 30s. Because the causes are unclear, no cure has been developed for the disease yet. The current treatment focuses on reducing inflammation, easing pain and controlling the immune system. Bang said the treatment differs depending on the severity and the location of the disease’s manifestations in each patient. “While some patients do not need any medication at all, others with serious symptoms have to take strong drugs like immunosuppressant and thalidomide, which could cause a teratogenicity or peripheral neuropathy as a side effect,” he said. “More than 40 types of drugs can be used for the disease’s management.” To share his treatment know-how with doctors in other parts of the world, Bang developed animal models of Behcet’s disease, which were published in 1998 on the European Journal of Dermatology. The models have been updated since. Thanks to his efforts, the rate of “the complete type” of Behcet’s disease, in which all the four main symptoms of oral ulcers, genital ulcers, skin lesions and ocular involvement appear, among patients in Korea have declined from 34.5 percent to 15 percent over the past 30 years. “The combination of earlier diagnosis, better oral hygiene and more informed doctors has probably affected the rate of the disease as well,” he said. One of his career goals is to find the causes and markers of Behcet’s disease. For years, Bang has been trying to prove that the alpha-enolase, a key glycolytic enzyme expressed in most tissues, is one of its markers.

Exploring the disease of less than 50 people

When Bang and his professor Lee Sung-nack established Korea’s first clinic dedicated only to Behcet’s disease at Yonsei University College of Medicine in 1983, there were fewer than 50 patients in the country. Today 15,000 patients with the disease are being treated, according to the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “This might mean that for a long time, many people suffered from the disease without knowing what they had,” Bang said. Believing that the real number of cases was much higher, Lee looked for a student who was interested in exploring the unknown area. “He offered me to study the field. I never knew this would be the beginning of my 40-year journey,” Bang said. “His offer really motivated me, and I thought it was an important job that someone must do.” While many of his medical school friends flew to the United States in the 1980s to study their fields, Bang went to Japan, where research about Behcet’s disease was more advanced. “The disease was the No. 1 cause of blindness among young Japanese during the 1970s, so the country’s ministry of health started to help researchers look into the disease,” he said. “I was fortunate to work with them there.” With 13 other doctors, Bang and Lee set up the Korean Society for Bechet’s Disease in 1999 and convinced the nation’s ministry of health to fund their research. While strengthening the doctors’ and patients’ networks for the disease, Bang and Lee also actively cooperated with other experts in other countries. Bang’s efforts have been recognized by researchers worldwide, and he has won several awards for his contribution to Behcet’s disease research. “Lee has greatly helped me get to where I am today,” Bang said. “I was fortunate to have an excellent teacher who showed me the way.” Unlike most other Bechet’s disease researchers who studied autoimmune rheumatic diseases, Bang is one of the very few dermatologists who chose to specialize in the field. He believes more dermatologists should join the global effort to conquer the disease. “Dermatologists could play a major role in discovering appropriate diagnosis methods because the disease usually starts with skin or mucosa problems,” Bang said. “As my research demonstrates, an early diagnosis is critical to ease the symptoms before they become very serious. Dermatologists are in the best position to do the job.”

댓글을 남겨주세요